(Click aquí para leer en Español)

(Click aquí para leer en Español)

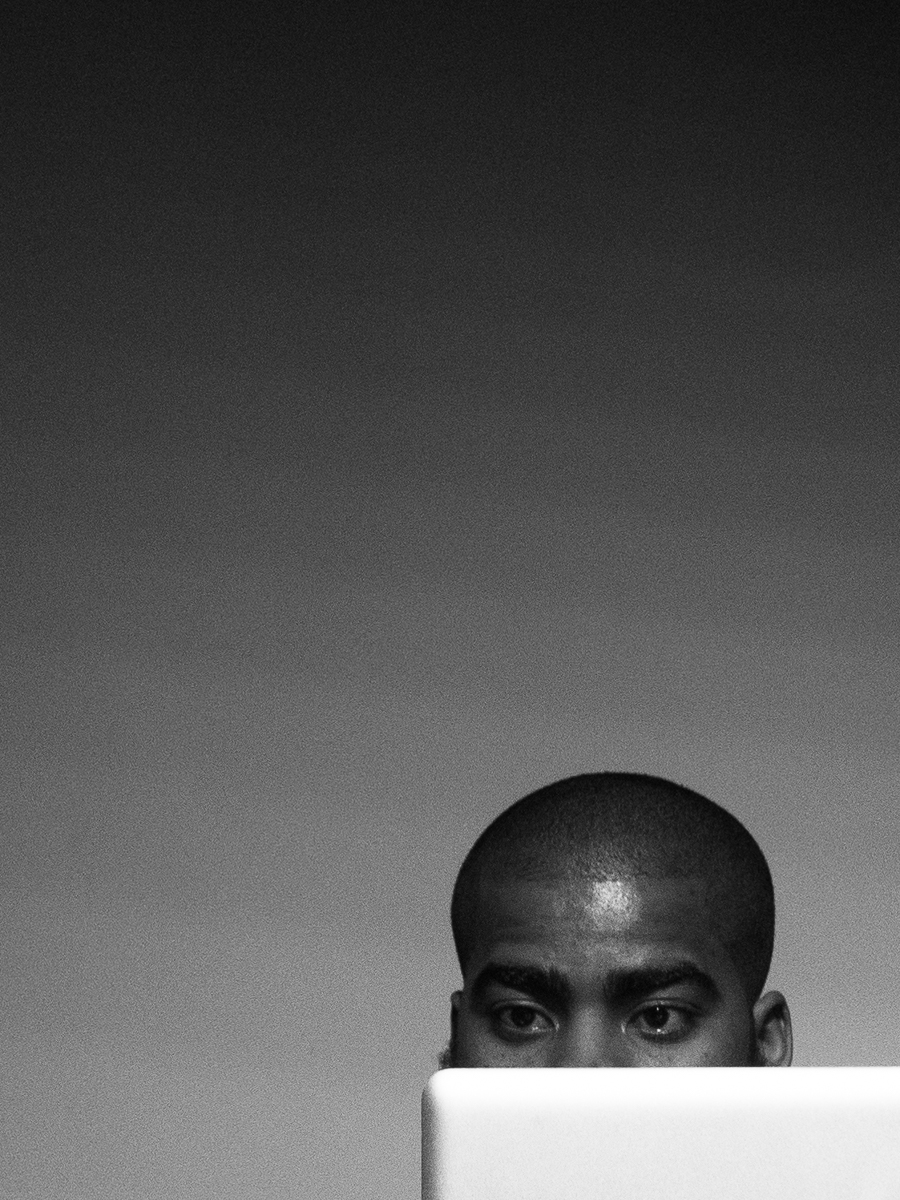

I never thought much of death. We all die. My sister died a young woman, when I was 17, and my mother when I was in my late 30’s. Both were deeply painful losses to me, becoming even more painful with the passing of time. But other than a very intimate feeling of bereavement and missing, and a continuous presence, as scars in my soul, if you will, I never really delved into it. And then, on March 1st, I was awakened to the news of my father passing in his sleep, probably right before dawn, 2200 miles away.

He was 89, and while it was something I sort of expected and was prepared for, death never fails to blind-side you.

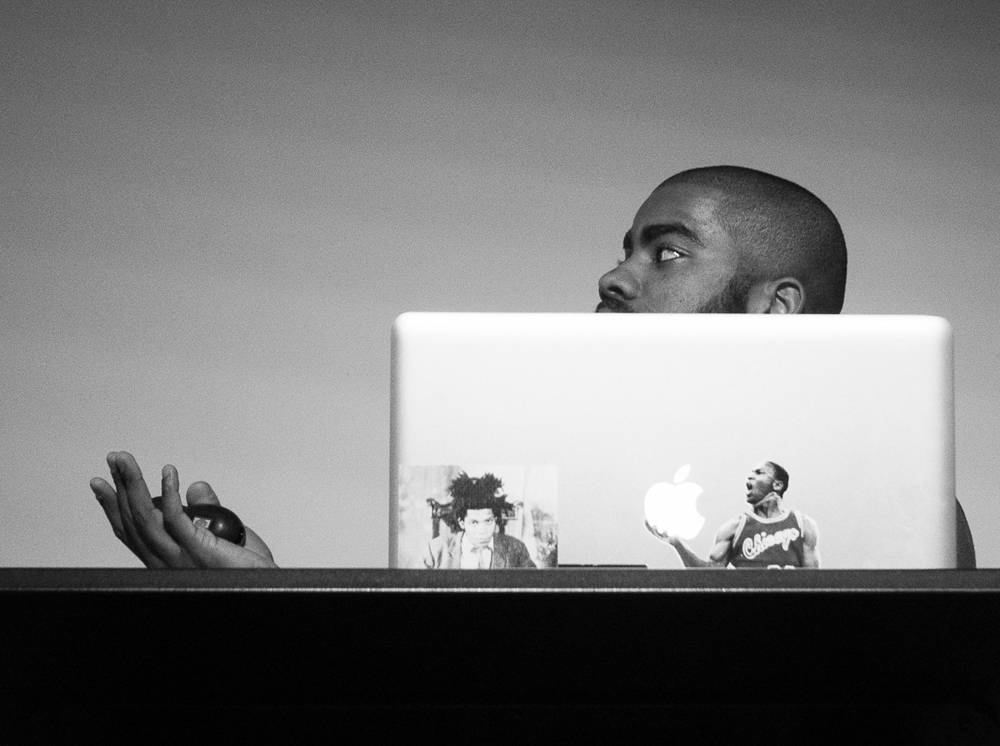

My father was a very special man. I’ve never met a person who could match his pessimism. Despair was his most prominent feature and having a son fascinated by downhill skiing, speleology, and scuba diving must’ve been quite a challenge for him. He mothered me to the point that I’d never fail to call him on Mothers’ instead of Fathers’ day.

On the flip-side, he was the luckiest person I’ve ever known: Most of his youth was snatched from him by war – first in Auschwitz, where he went only at his mother’s insistence to stay with the family, for he really wanted to join the resistance and fight the Germans, and then in 1948, as soon as he landed in Israel after spending a year in a British detention camp for illegal immigrants in Cyprus. He nearly died from an infection after eating a dead horse’s raw flesh while doing forced labor, he was shot, he emerged unscathed from a knife-fight while in combat, he got a job as a lifeguard in spite of not knowing how to swim (he learned later), he found out he had just survived a heart-attack after walking for about two hours with chest pain to see his doctor, he suffered a stroke in 2010, but his cognitive abilities were left intact and recovered almost completely in about a year, the woman that cared for him for the last four years of his life turned out to be an angel, and, as if in a final streak of luck, he died peacefully, in his sleep, on March 1, 2015, with no signs of pain or suffering.

Flying from New York to Caracas takes about 14 hours and, in my case, it meant leaving JFK in the afternoon and spending the night at the airport in Trinidad to arrive the following morning.

My father’s house felt strange without him. Not empty, as it’s filled with my parents’ things and their memories. The only other time I arrived at this apartment to be the only person in it was when my mother was hospitalized, in 2002, a few days before she died.

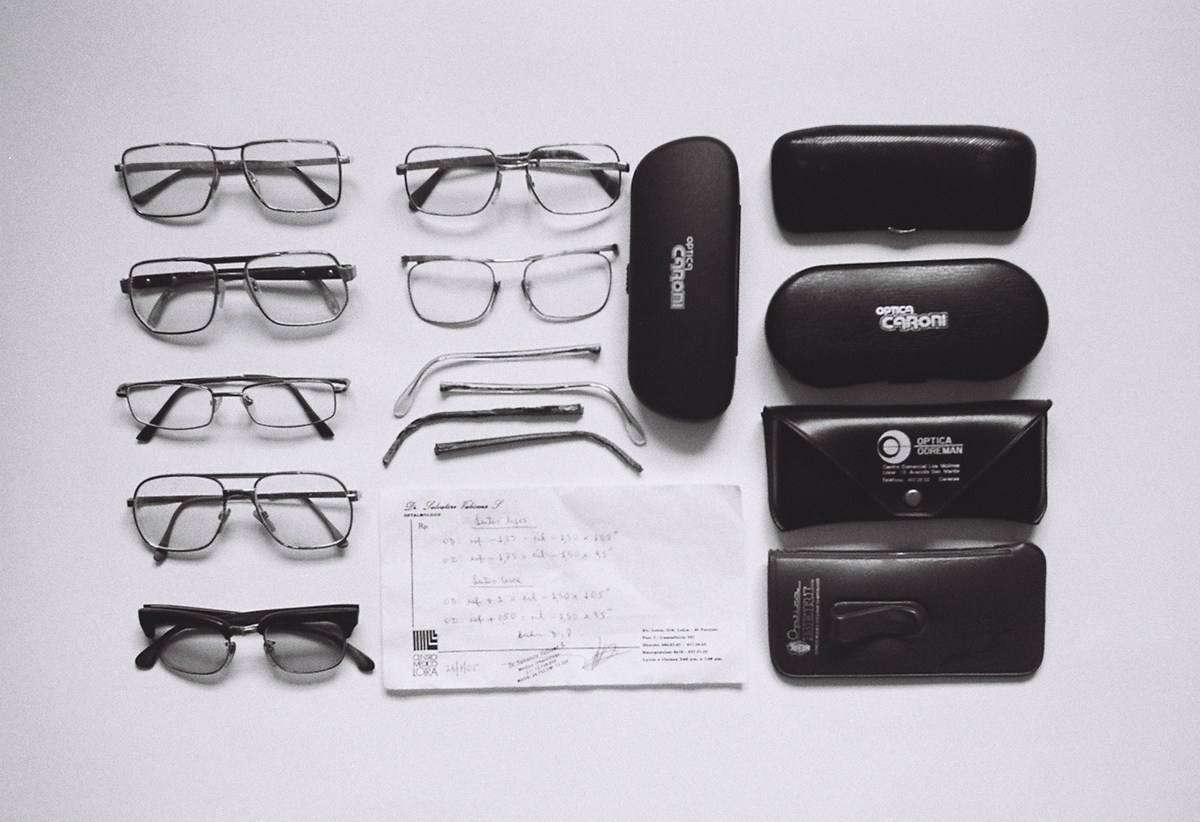

He’s buried now. It feels very strange to write this. I’ve spent the past days rummaging through his things while I set his affairs in order, and as I go through drawers and closets filled to capacity with knick-knacks and old bills, I find my father, and the image of him that develops is made up of fragments that are familiar and fragments that aren’t. I find myself in his inability to let go of old, now useless, documents and bills, many more scissors than things to cut with them, screws, electrical parts that no longer work, pictures, tools, ID-cards and countless copies of them, letters, pens, porn, dentures, eye-glasses. Much of what I find reminds me of what I’ve accumulated: I too own a few pounds of rusty screws and nuts “’cause you never know when you’ll need one,” computer parts, even two zipper pullers that I ought to throw away because it’s clear that I’ll never find any use for them.

His whole life, or the parts that he treasured, at least, is strewn everywhere and even though I’m sure there was a method to this madness, it fails to materialize before my eyes. I find things that I know of but I also find things that are new to me, and most importantly, things that yield raw details about him that I didn’t know: he was far more meticulous than I ever knew – there are electrical diagrams drawn and annotated using four different colors. He kept painstakingly detailed ledgers of the daily activity of all the businesses he ever owned. I thought he was just part-owner of Venezuela’s most iconic ice-cream business when I was growing up, but the truth is that he loved his work and was a master at it – I found eight different recipes for vanilla ice-cream alone! (Crema Paraiso’s web site, not surprisingly, fails to mention him or my uncle Henry as the two men who actually built that business when their cousin decided to abandon ship shortly after founding it and move to another country with his family – yes, I’m very angry about this, have been for a long time, and as I mourn my dad, I feel entitled to say whatever’s on my mind.)

We Jews are supposed to sit for a week after a loved one dies, which I had to forego because I’m my father’s sole survivor and I don’t live here, and my time is very limited. As I’m overwhelmed and exhausted by answering the same questions over and over again, by paperwork and loose ends crying to be tied, I begin to appreciate the importance of the ritual as a way to ease into the loss and also ease out of it. Somehow, this photographic journey into my father’s intimate possessions gave me a chance to mourn him in my own way – by getting to know him again. Touching every item and reflecting on it as I carefully arranged his drawers’ contents to photograph them gave me one more chance to be with him as I hadn’t been since I was a child and he was my hero, and in some regards, he has regained his heroic aura in my eyes.

The thought of diving into this from a photographic perspective only came to me as I was frantically packing for the trip and, inspired by David Brommer’s approach to photographing WWII battlefields with an 8 x 10 camera, I felt that I owed it to my dad to go with film, using that first camera he bought for me in 1976, when I was twelve, which was still sitting in his bedroom closet.

What this is, really, is an autopsy of his soul and, even though I know I will come out of this with a better understanding of who my father really was, I will never know him as his peers did or the people who grew up with him. There are conversations a son will never have with his father, and even though I would love nothing more than to learn more about him, I am at peace with this. I know that even if he were alive, there will always be things I wouldn’t be able to bring myself to ask, things he would never tell me, because that’s just the way it is. Yet, I still want to piece together as much as I can before I toss a lifetime of useless things and put aside a handful of tokens I will treasure and pass on, the things he treasured, the things he used, the things he couldn’t get rid of, before I embark on the long trip back to my family, to my wife and my daughter, who are my home.

3 Comments

Wonderful, sensitive piece Alex. Thanks for sharing, especially during this week leading up to Father’s Day. Creative way of telling the reader about your dad and about you as well.

Thank you so much, Alan!!!

Hi

I just came across you blog when I was too lazy to type in the url to mine and instead used Google. Really enjoyed reading this.

Funnily enough, my blog is also entiled ‘Dad’s Drawers’ and has a eerily similar theme. I started mine after my dad died in 2011 with thoughts of keeping a photographic record of all his various hoards/collections of bits and pieces in a variety of drawers. The blog turned into a bit more than just photographs, and started to include stories of growing up with an unconventional dad. My father too was an Austrian Jew, lucky enough to escape from Austria just before the rest of his family were rounded up. He to spent many of the war years in internment camps in France, Spain and Israel. He finally ended up here in the UK.

I found (and still find) that the blog helped the grieving process and I have been lucky enough to be able to clear through his stuff at a fairly slow pace as my mum still lives in the family home.

If you are interested, my blog can be found on wordpress as is entitled ‘Dad’s Drawers’ -A lifetime of Hoarding.