Photography, by itself, depending on who takes the photograph or photographs, is either all art or half art and half science. Its scientific component may be more or less present (or even absent altogether), depending on who’s behind the camera. If you hand a camera to a 6-year-old, with a yen for drawing or painting, you will get a pure, fully artistic approach to capturing images. He or she can’t be bothered with non-sense such as aperture, speed, or even focus; if the child has an instinctive idea of what looks good and what doesn’t, or an inkling of what works in terms of composition, the pictures may be blurred, out of focus, over or under-exposed, but they will be good pictures. With adults, the mix tends to be more even, but there will still be variations on what they’re more interested in at the moment of depressing the button.

Ironic as it may seem, our ability to see, something we’re all born with, needs to be relearned for some odd reason.

It’s very uncommon for a single photograph, in spite of high artistic value, to be called art.

Taking artful photographs is an art. However, that doesn’t automatically make your photography art. At least not by the tacit, but never uttered, concept that curators, judges, collectors, or, in other words, the art community holds dear. Even the most commercial of photographers knows this, and this is where the similarities between good photographer and photographer as artist end.

In one of those strange twists in history, the cellular revolution caused an explosion in the world of photography, to the point, to some extent, of commodification – it’s nearly impossible now to find anyone older than 14 in the developed world who doesn’t carry a camera at all times: phones, and by extension, cameras are beyond ubiquitous. They have become things we wear, like pants, shirts, and shoes.

Nowadays, we carry cameras whether we want to or not, and the traditional cost of photography is now optional. As a result, the number of photographs taken every day is incredibly large. Based on the 10,000 monkeys theory alone, without delving into statistics, it’s obvious that every day, a staggering number of truly extraordinary photographs are produced, many of which are artistic by nature. Yet, as I said, they aren’t necessarily art. Even without looking at every good photograph that’s out there, you can see this by yourself by visiting instagram, flikr, 500px, and other similar sites, where a community regularly promotes a smaller, manageable, set of them to “pictures of the day” and other such titles. Very rarely these single successes travel beyond the virtual borders of the internet and onto the walls of galleries or into the pages of books devoted to photography.

The cost of entry into this world is high, it’s riddled with obstacles (none of them unsurmountable, just so you’re aware of it, but not at all easy to overcome) and involves considerable time and friction from both, internal and external sources. For those who follow the academic route, at least in the US, with the average BFA or MFA, from what I’ve looked at, costing around $50,000, it becomes quantifiable and, at the end of it, you will own a degree that’s less than marketable in the “normal” job market, so now you’re also deep in debt already at the outset. The world of academia, however, has one very clear, and considerable, advantage: by the time you graduate, you will already have made a lot of mistakes, will have spent Malcolm Gladwell’s proverbial 10,000 hours honing your craft, will receive guidance from art world personalities, your work is likely to already have been seen, and you will already have made a number of excellent contacts that have the power to further your career. But for now, let’s get back to the discussion at hand. I’ll write some other time about the academic path…

But what makes it art?

The work of an artist is never a single work of art. It’s usually a whole body of work and, generally, it spans years of careful tending. As cold as it may sound, there’s also a business, or less artistic and more planned, side to it, which has less to do with the craft itself and more with how it’s presented. Successful individuals who achieve artistic recognition during their lifetimes do so by paying close attention to both aspects of their careers, just like a store owner or someone intending to bring their company from a damp basement to Wall St. It would be nice for a painter to just be able to spend every hour of every work day painting, or for a photographer to just devote all of her or his energy to capturing fleeting moments, but the reality is, well, in lieu of a better word, real. Far more real than that.

The “one-hit wonder” we’ve grown accustomed to see in the music industry doesn’t seem to exist in the world of art, and even in the former, nobody in their right mind decides that they want to be a one-hit wonder; at least not going in.

In essence, a lot more than we, as photographers, would like hinges on what we do when we’re not working directly with photography, whether it’s taking pictures, editing, or retouching. Or preparing work for reviews, gallery submissions, or contests, among a plethora of other, more mundane, tasks.

That’s not to say, however, that there isn’t much of the actual artistic work that needs careful planning and thinking in order for it to be generally accepted as art and not as merely a collection of good, or even stunning, photographs. Like I said before, in another article, several dozens worth of amazing photographs, or even hundreds of them, on an instagram page aren’t the same as having an actual body of work that’s recognizable as such from an artistic perspective. You still need to work on your work.

If you visit artists’ web sites, or peruse the images of their gallery shows, you will notice a common thread: cohesion.

Images are grouped in collections, projects, or series, and in some cases the style is so constant that after looking at some artists’ images for a while, you begin to recognize them. This is very much in contrast to the mish-mash that is the average instagram, 500px, or flikr page. Very much so.

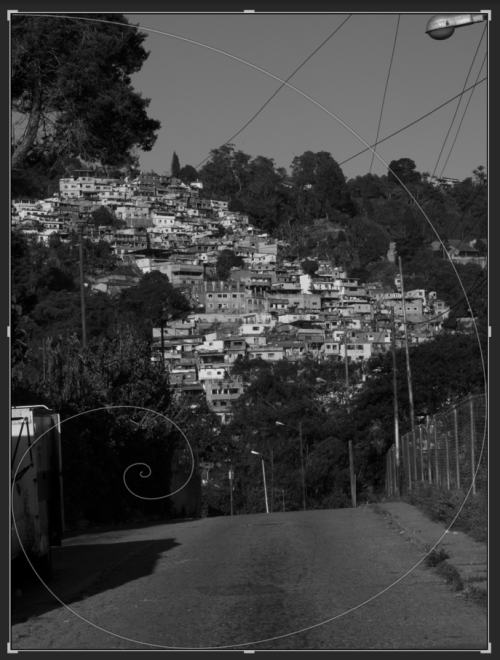

Andre Wagner is a documentary photographer who concentrates on what he encounters in his own neighborhood (picturesque Bushwick, in Brooklyn, NY) or wherever his travels take him. As such, he has no control over what he will encounter. His photography’s connecting thread is his style (strictly documentary) and, to a lesser degree, his medium (film).

In Klaus-Peter Statz‘s own words: “I have been to Berlin many times and it took me several attempts to get these shots.” The subject in these images remains constant. However, the commonality is so evident in all of them that it’s impossible not to recognize the common thread in all the images.

Another photographer whose style is highly recognizable is Carol Julienne. Her photographs’ super-high contrast jumps at you, but that alone doesn’t make them special. The images themselves, even without the extreme contrast are interesting to begin with.

In all the samples above, it’s clear, even to someone who knows nothing about photography that there’s a commonality among the images of each photographer. And while we all like to just be out with the camera or at the studio and hope to capture an extraordinary moment, and often do it successfully, it’s important to present the work in a cohesive, rational, and, yes, predictable, manner. In marketing, this is called “packaging,” and A LOT of thought goes into it. The product of your work shouldn’t be treated differently.

Presentation has a lot to do with the audience. If all you’re looking for is a stream of “likes” in social media, there’s no need to mind any of this. With a large enough following, you will get there just by showcasing great photographs. In the art world, however, it’s important that you show consideration for your audience: they’re accustomed to series or project-based work, to the cohesion I’m referring to here. If you point them to an eclectic collection of images, they will appreciate the quality of the images, recognize the few outstanding ones, and move on, as what they expect to see just isn’t there. By consideration, I don’t mean “be nice.” I mean “really consider who they are.”

Thinking like a gallery owner, curator, or collector is not easy, however. Otherwise, curators would be a dime a dozen. To make things even more challenging, I can’t imagine many tasks as difficult as editing or curating one’s own body of work: it’s nearly impossible to detach oneself emotionally from one’s work and judge from a place of neutrality. It’s like having to pick one child over another (or one mistress over another, for those who enjoy dangerous lives). The best you can possibly do is identify which images are cohesive enough to represent a series or project and which aren’t. And if you haven’t looked at all your body of work in a single sitting (which might easily take an entire day or more), you should: sometimes, something that only your subconscious knows about your personal collection is very likely to surface and become evident. You will get to know your photographic self better after doing this exercise. Exhausting as it is, it’s a good idea to repeat periodically periodically. The more images you manage to find this way, the easier it becomes (“easy” being, still, quite the understatement), due to style and other, less obvious, traits coming to light as you do it. In the digital age, this problem is compounded by larger number of images you will need to go through, as opposed to what used to be the case, when almost no one would take more than 100 or so photographs in a single day and the associated costs of shooting film could easily get out of hand. But it is what it is, and, again, you should do it.

A good, albeit imperfect, alternative to pick these individuals’ brains directly is to follow them (online or off): read anything written by them, and take a close, cold, analytical view at any work they curate or even mention (good or bad, it doesn’t matter – you’re after information here, not assurances). You will slowly gain a pretty good grasp on what works for them and what doesn’t. Know your audience, like I mentioned in another article: the more you know about it, the better chances you have of making an impression. And this exercise has no downside: even an adverse review will yield invaluable information and feedback. And if it’s a review about your work, more power to you!

As you “stalk your prey,” it’s essential to pay as much attention to what they react to as to what doesn’t elicit a reaction, because most likely, your work falls into the latter category, and if this is the case, it’s time to move on and look elsewhere. It’s important to let go of the fact that not everybody will like your photography. Otherwise, you will suffer. A lot.

This, however, is a very difficult task: The more passionate you are, the harder it becomes to deal with rejection. The natural conclusion from this is that in order not to be terribly affected by the latter, you must allay the former. And this has the potential of affecting your art. Now, don’t take me wrong; I am passionate about what I do, but I don’t subscribe to the “drop everything and follow your passions” school of thought. Reality almost never permits this, at least not in a literal and immediate sense, but then, every person’s current reality is the result of past decisions. If you want that to change, you have to craft your choices accordingly, but it won’t change immediately; you must remember that life’s not like a Stir Fry but rather like a Spanish Paella and change takes place at its own, slow, pace.

You’re trying to make it as an artist precisely due to passional reasons, and it’s this passion which compels you to create (whether it’s painting or photographing or playing an instrument or any artistic endeavor). If you manage to get to the point of rejection not affecting you one bit, there’s a possibility that your art, which is fueled by this very passion, will be affected by your new, saner, attitude, so this is something to watch out for.

Refining your technique requires time. Reviews. Critiques. Networking with galleries, making yourself known.

The Chinese have a saying: “The best two days to plant a tree are twenty years ago and today.” Now go get a shovel and start digging.