Photography is a dialogue between subject and photographer. The camera only serves as a device to capture this conversation and freeze it in time.

Photography is a dialogue between subject and photographer. The camera only serves as a device to capture this conversation and freeze it in time.

It goes well beyond seeing something and taking its picture, and in the instant that it takes for the light to make an impression on your camera’s film or sensor, there’s as much coming from the front as there is from the back. This was pointed out to me by a childhood friend, Gregor Barschi, who takes great photographs with whichever phone’s in his pocket when he sees (and seizes) the opportunity. Being an important art collector, and having done so for some thirty years, has honed his eye; and being analytical by nature has honed his understanding of what transpires between photographer, camera, and subject when the button is pressed.

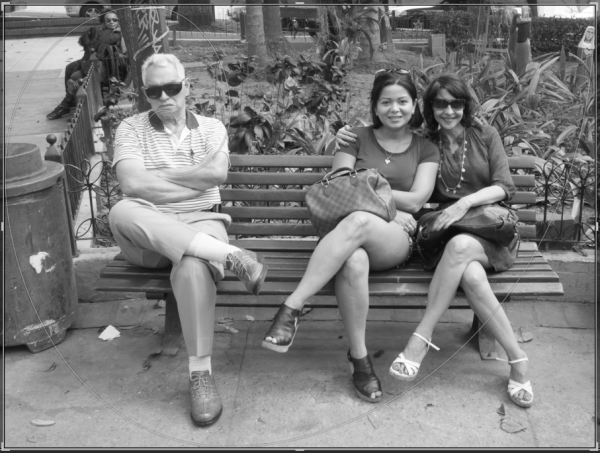

Successful fashion and portrait photographers know this better than anyone and their career success actually hinges on this detail as much as it does on their artistic abilities.

The emotional charge of an image depends on its subject and at the same time on the photographer’s ability to notice it. It’s a two-way street.

When there’s a disconnect between the two, the camera captures this just as well. It’s as simple as that. And at some subconscious level, it becomes blatantly obvious even to the untrained eye – you can tell when a photographer and a model aren’t getting along (if you are lucky enough to see such pictures), even if you couldn’t put in words what it is that makes the image unappealing or unsuccessful, if you’re into using more precise language. Someone who doesn’t care about malnutrition, to use an extreme example, will go to Africa and take pictures that will show malnourished children in a number of settings and poses. Someone that is deeply moved by the problem, however, will go to Africa and come back not with pictures of children, but with images of malnutrition itself.

“But what about street photography or architecture?” you’re probably asking at this point. Or landscape photography. Or any number of genres (and there are a lot of them out there, believe me) in which there isn’t an evidently bidirectional exchange?

It’s exactly the same. The fact that your subject isn’t capable of expressing emotions doesn’t mean that it can’t elicit them. On the contrary, it does, and quite strongly, I must add.

At a recent lecture by landscape photographer Tim Cooper, he said something that sums it all up: “I love to be outdoors.” And his landscapes transmit just this. When you look at his images, you see what he sees, how he sees, and how it moves him. Me? I like being outdoors in the wild, so while my landscape photography would enjoy good execution and be technically sound, it would only show mountains, rivers, and the occasional snake.

Architecture is the landscape facet of human creation, and photographing it also demands fascination and awe to be successful, to be able to present it in a way that not only transmits its beauty to the viewer but turns the photographer’s emotions about it into something visible, tangible. Photographing buildings isn’t architectural photography, and architectural photography is much more than this (or less, if you’re into Mies Van Der Rohe et al).

And, skipping over a good dozen themes, I must touch on street photography as well, because that’s one of the two genres I practice the most these days. I love urban. I love the feeling that walking elicits between he or she who walks and the city walked on. I didn’t know this 25 years ago, but now that I think of it, this feeling of urban intimacy which I wasn’t able to experience in my native Caracas because I was always in a car, played a very important role in my relocation even though at the time this was all alien to me.

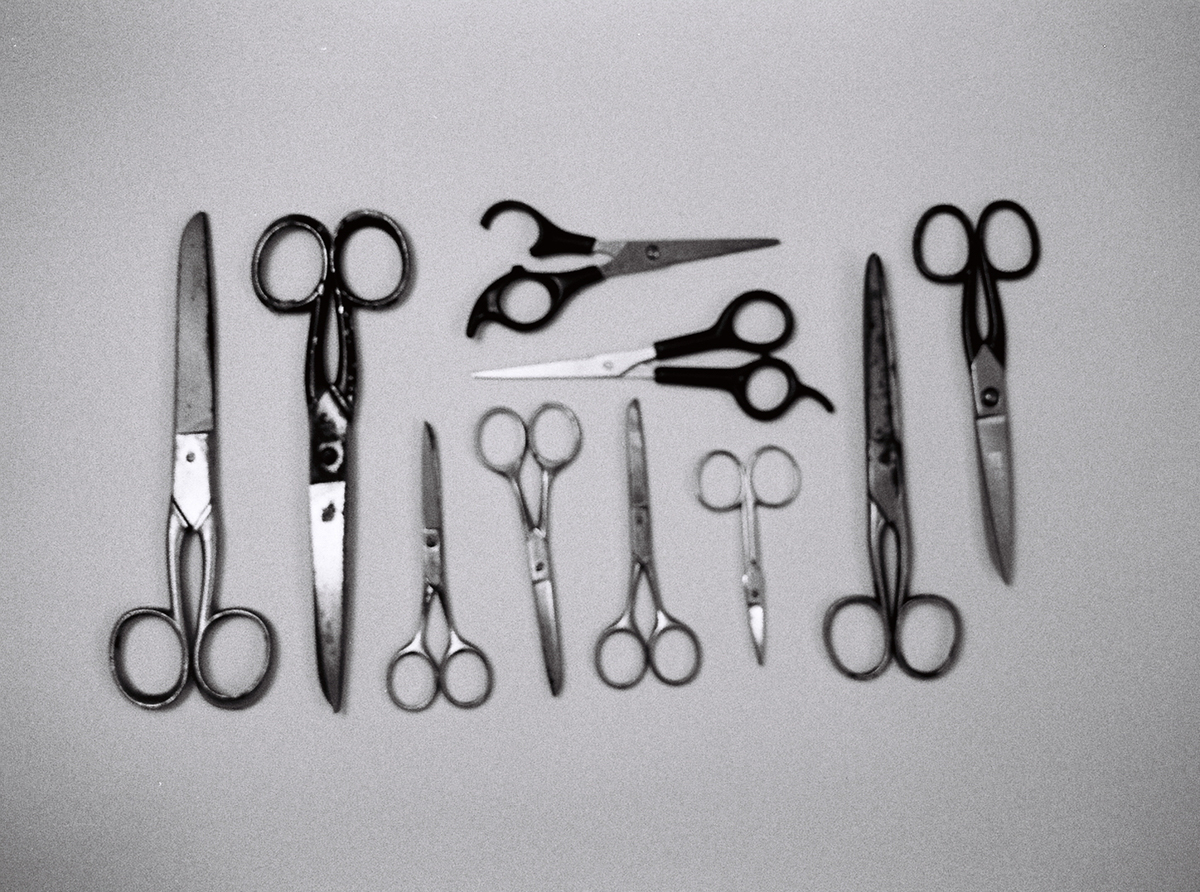

Street photography shares the opportunism of wild-life photography, and in many ways it’s possible to draw parallels between the two. “Life in its natural environment” is but a pretty way of saying “people going about their business in the street.” I like people-watching as much as others enjoy going to a safari. The human fauna is varied and fascinating and much of what they do, they do without paying attention to how spectacularly they do it, and this is the “eye” that I’ve found in me, and this is what I see and photograph. Is there interaction between my subjects and me? It depends. Sometimes there is, sometimes there isn’t. Some times the voyeur in me takes over and I want to be as noticeable as a mailbox. Other times I almost want the person I’m photographing to know that a fraction of an instant after they realize I’m looking at them, I will have taken their picture.

It is important that you like what you photograph or, more appropriately (because I can’t imagine anyone liking malnutrition) that you are into it. Very much. If photography were invented by Buddhist monks, it would be written somewhere that you must “be one with what you’re photographing.”