To put it mildly, a critique is a daunting event. It involves countless hours of preparation, each and every minute of which is filled with heavy doses of self-doubt, trepidation, and uncertainty. Unless you can predict the future or read minds, there is very little (if at all, if you’re lucky) that’s objective about them. If you don’t believe this, pick ten random images from your archives, show them to a few random people (especially strangers), write down the results, and tabulate. Even if there is a semblance of consensus, chances are that doing the same exercise with professional critics will yield completely different results. Perception and opinion are as personal as they can get. Young critics will view things differently than older, more seasoned ones. Education, culture, and experience also play important roles on what someone finds laudable. In essence, it’s a crap-shot, and no amount of planning will yield reproducible results.

To put it mildly, a critique is a daunting event. It involves countless hours of preparation, each and every minute of which is filled with heavy doses of self-doubt, trepidation, and uncertainty. Unless you can predict the future or read minds, there is very little (if at all, if you’re lucky) that’s objective about them. If you don’t believe this, pick ten random images from your archives, show them to a few random people (especially strangers), write down the results, and tabulate. Even if there is a semblance of consensus, chances are that doing the same exercise with professional critics will yield completely different results. Perception and opinion are as personal as they can get. Young critics will view things differently than older, more seasoned ones. Education, culture, and experience also play important roles on what someone finds laudable. In essence, it’s a crap-shot, and no amount of planning will yield reproducible results.

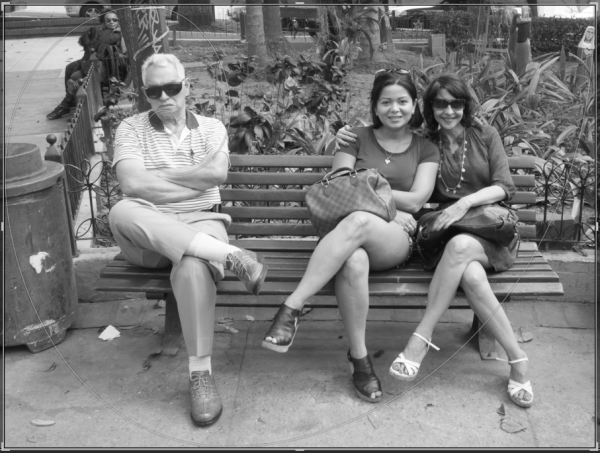

However, not all is bad. The more critiques you expose yourself to, the more likely you are to hone your ability not to take things personally (even though I can hardly think of anything more personal than one’s art). Seriously, though, at some very visceral level you will start to develop a sense of direction. A sensitivity to what, for most critics, is desirable. From my own experience and observation I can say, with some degree of property, that one thing that comes up consistently in artistic environments is work identity: it doesn’t make sense to mix things up – it confuses your audience – so it’s important to group your work somehow. And I’m not talking about style or process (although the latter takes center stage if it’s integral to your oeuvre). I’m referring to series and projects (i.e. having an image of a horse among a dozen images of birds is a deal-breaker), in which there is a common thread that ties everything together. Even if 90% of what you do is interventionism, visual consistency is a very important consideration. It all boils down to context. And the less you have to explain the better, for it’s very easy to break a critic’s perceived mood by volunteering an explanation that takes her or him completely off-guard.

In a typical critique or review, you will have about ten minutes to present your portfolio to one reviewer before you move on to the next. Each of these reviews will be a unique experience with regards to which images are well-received and which aren’t, and at the end of the event, if you paid attention, at the very least, you will be able to recognize one or more trends on how your work (or parts of it) is received.

The other type of review I’ve been to, which I find much harder to prepare to, involves one or two reviewers going over the work of a few dozen artists in one fell swoop in a short period of time. The difficulty, for me, arises from the fact that in this case, I can’t present more than three photographs: I have to decide whether to burn that cartridge with three images from a single series or show three samples of three different series, or show three unrelated images in the hope that each of them can stand on their own merits. In a way, this last option is similar to posting single images on facebook or instagram – your contacts will “like” or ignore, but the bottom line is that the audience reacts to the work one image at a time in this environment.

And that’s what will keep you up on the eve of your next crit.